What do you do when you are sailing offshore and you find yourself in a storm? How can you deal with storms so you don't break expensive gear and people don't get hurt?

Storm management for cruisers is mostly common sense and is within the ability of ordinary people who venture offshore in seaworthy yachts.

Storm management is all about energy management. Large storms have lots of energy, and you need to learn how to deal safely with all that energy if you want to stay out of harms way.

Storm management is actually energy management. If the energy in a storm gets transferred to your yacht - coupled to your sailboat - then you have to safely dissipate all that energy so that nothing bad happens.

Most people don't understand the physics of storms and how they couple energy to your yacht. The basic concept is this: A storm contains massive amounts of energy, but if you don't let that energy climb on board your yacht, you will fare well during a storm. Conversely, if you sail in an uncontrolled and dangerous manner allowing the storm to couple its destructive energy to your yacht, then don't be surprised if you or your yacht are hurt.

First, let's talk about energy in a simple way so you can understand the magnitude of the forces at work in a storm. What you need to understand is the amount of energy in your yacht. I will give you a simple scale of relative energy that is easy to understand.

To create this energy scale, you need some simple mathematics to comprehend what's happening. Here is a formula that puts things in perspective:

KE = 1/2 Mass x Velocity Squared

This equation states that the kinetic energy of your yacht is equal to one half the mass of your yacht multiplied by the square of your yacht's speed. When you look at this equation, you can pretty much ignore the mass of your vessel because it isn't going to change significantly during a storm unless you throw things overboard and lighten ship.

If you ignore the mass of your boat, the equation becomes KE = Velocity Squared. This simplified equation works well for purposes of our discussion. The equation means that the amount of energy your boat has to safely dissipate is directly related to the square of the speed of your yacht. If you double the speed, the kinetic energy goes up four times.

Check out these numbers to see how the relative kinetic energy of your vessel changes with your speed.

YACHT SPEED = 0 KINETIC ENERGY = 0

YACHT SPEED = 1 KINETIC ENERGY = 1

YACHT SPEED = 2 KINETIC ENERGY = 4

YACHT SPEED = 3 KINETIC ENERGY = 9

YACHT SPEED = 4 KINETIC ENERGY = 16

YACHT SPEED = 5 KINETIC ENERGY = 25

YACHT SPEED = 6 KINETIC ENERGY = 36

YACHT SPEED = 7 KINETIC ENERGY = 49

YACHT SPEED = 8 KINETIC ENERGY = 64

YACHT SPEED = 9 KINETIC ENERGY = 81

YACHT SPEED =10 KINETIC ENERGY = 100

YACHT SPEED =12 KINETIC ENERGY = 144

YACHT SPEED =16 KINETIC ENERGY = 256

YACHT SPEED =20 KINETIC ENERGY = 400

This scale that shows the relative amount of kinetic energy you have on board at different speeds. You can see that when your yacht speed is zero, you have essentially zero kinetic energy. At one knot, you have one unit of kinetic energy, at four knots you have 16 units of kinetic energy, at eight knots you have 64 units of kinetic energy, and at 16 knots of boat speed you have 256 units of kinetic energy on board.

When my sailboat was surfing at eighteen knots in the Atlantic Ocean during a storm, I had to safely dissipate 324 units of kinetic energy to stay out of trouble. My catamaran was going so fast and had so much energy on board that the slightest mistake by the helmsman or autopilot could result in personal injury, damage to the yacht, broach, or even capsize.

When your speed gets out of control, the kinetic energy rises astronomically, and you better not make a mistake, because all that energy is going to hurt you. This relative scale of kinetic energy shows that when you are hove to or lying to a parachute during a storm, the kinetic energy of your yacht is close to zero. When you are running downwind trailing a drogue at a few knots in a controlled manner, your kinetic energy remains at safe levels. But when you are sailing along at eight knots and surfing down the faces of waves at eighteen knots, you are courting disaster because if you lose control of all that energy and dissipate it in an unsafe manner, bad things are going to happen to you and your yacht.

STORM MANAGEMENT IS ALL ABOUT ENERGY MANAGEMENT

1. Uncontrolled energy is what destroys yachts during a storm. Yachts get going too fast, and then lose control and broach. Yachts with high levels of kinetic energy jump off the crests of waves into the troughs and the uncontrolled energy breaks bulkheads loose and destroys rigs. Yachts with high levels of energy sail into walls of water (called waves) and their yacht shudders from stem to stern as they crash into the seas.

2. Yachts that safely dissipate their kinetic energy survive storms without damage. You must monitor and control the energy in your yacht so that it never reaches dangerous levels.

3. If you are not careful, stormy seas and strong winds will transfer their energy to your yacht, and when that energy reaches dangerous levels, bad things will happen. Rudders break off, yachts roll and pitchpole, masts come down, and people sustain injuries.

YOUR JOB IN A STORM

1. Position your yacht in a location so that it's exposed to the least amount of energy. Storm avoidance or at least positioning yourself in the "safe" semicircle will do a lot to limit the amount of energy that you have to deal with in a storm.

2. Once you find yourself in a storm, you must decouple the energy of the storm from your yacht. Just because the wind is blowing fifty knots and there are twenty foot seas doesn't mean that all of that energy has to climb on board your yacht. You can heave to, use drogues or even parachutes to decouple the energy of the storm from your yacht.

3. Reduce your yacht's energy (speed) to the smallest amount possible consistent with good seamanship. When you stop your yacht or reduce its speed, you are stepping away from the edge of disaster. You are saying goodbye to brinksmanship and hello to good seamanship.

NON-BREAKING SEAS

Inexperienced mariners need to understand that in non-breakings seas, water doesn't move horizontally. It moves vertically. There is no horizontal displacement of the water in a non-breaking wave. If you look at a single molecule of water in a wave, the water molecule moves up and down in a trochoidal pattern rather than moving in a horizontal direction. In non-breaking waves, the water molecules are riding an elevator up and down as the energy wave passes through the sea. When you watch the oncoming waves in a storm, it's not water that is coming toward you, it's an energy wave that's moving in your direction. The water molecules are just moving up and down, whereas, the energy wave is moving toward you at 20 - 25 knots. As long as you don't couple all that energy to your yacht, the energy will pass harmlessly under your hull. But if you start sailing and decide to surf down the front of the energy wave, then you can couple large amounts of wave energy to your yacht and it can even reach dangerous levels that can cause you to broach. In non-breaking seas, if you don't couple into the energy wave, you will do fine.

In non-breaking seas, there is no excuse for getting into trouble. If you get hurt, it's because you have made bad choices that allowed your yacht to couple into the energy of the non-breaking seas. You are guilty of pilot error and any damage that you sustain was preventable.

BREAKING SEAS

Breaking seas are an entirely different story. There is horizontal displacement of tons of water heading straight for your yacht. When all that water hits your yacht, it transfers massive amounts of energy to your hull, and if you can't dissipate that energy in a safe manner, big problems will happen.

To deal with breaking seas, you must prevent or minimize the energy couple between the seas and your yacht. That's where parachutes and series drogues can save you. They can keep your kinetic energy at close to zero and decouple the energy of the seas from your yacht. Parachutes essentially stop your yacht and reduce the kinetic energy of your yacht to zero. Parachutes also keep the bow of your yacht into the seas (easily done in a catamaran) and this reduces the coupling of storm's energy to your yacht as well. The bows present a small surface area to the sea and makes it more difficult for seas to transfer their energy to your boat.

A series drogue will slow you down to a few knots, and if a massive wave strike happens, it will hopefully keep your kinetic energy at safe levels.

Breaking seas are dangerous, and only good seamanship will get you safely through a storm with large breaking waves. When the breaking seas get really big, you better have your parachute in the water or be towing a powerful drogue behind your yacht.

STAY OUT OF BLACK HOLES WHERE PEOPLE GET HURT YEAR AFTER YEAR

People frequently and predictably get hurt in "black holes" every year. These places include the Agulhas current in the Mozambique Channel, the Agulhas Plateau, the Gulf Stream, the no mans land between New Zealand and the South Pacific, and the Tasman Sea. These and other black holes can swallow you up without a trace. If your boat and crew are not up to sailing through black holes, don't go there. You can sail all the way around the world in the trade winds without sailing into any black holes if you go up the Red Sea.

DEALING WITH BLACK HOLES

1. You need to have a working engine in good condition to push the odds in your favor.

2. You need lots of fuel.

3. Synchronize with a weather window.

4. Turn around, hold position, or alter course if conditions are deteriorating.

5. Stay to one side of any storm coming your way.

6. Have drogues and parachutes prepared ahead of time and ready to go.

Two times I sailed through black holes from Fiji to New Zealand. Both times I had a good trip because I left Fiji on the back side of a low, and then I motor sailed through the oncoming high, and I arrived in New Zealand just before the next low pressure system came across the Tasman with stormy seas. Those people who refused to use their engines and instead sailed all the way to New Zealand ended up taking ten days for the voyage rather than seven, and many of them suffered damage en route. Each year that we made the trip, there were one to three people lost in stormy seas. On our first trip, a steel yacht was rolled and a family of four was run down by a ship in stormy seas with the loss of three lives.

When I head through a black hole, I don't dilly dally. I put the hammer down, and if there isn't sufficient wind, I turn on my engine because I don't want to spend any time longer than necessary sailing through black holes. When I know that I am going to sail through a black hole, I pre-rig my parachute bridle on the bows so that it is ready to go if I need it. I also pull all of my drogues, parachutes, tethers, floats, rodes, and bridles out of the lockers before I set sail, and I put them on the cabin sole in my salon where they are easily accessible. I put a couple of cushions on the pile of safety gear, and I make a large bunk out of it. If it becomes necessary to deploy a parachute or a drogue, I move the gear to the cockpit where I assemble all the components for rapid and easy deployment.

IT'S NOT THE WIND THAT WILL GET YOU IN A STORM. IT'S THE SEAS THAT WILL CAUSE THE BIGGEST PROBLEMS. STAY TO ONE SIDE OF STORM TRACKS SO THAT YOU GET SEAS MOSTLY OUT OF ONE QUADRANT.

Moitessier's Plan - When sailing in the southern ocean, he sailed away from the path of the oncoming gale for the first half of the storm, and then he turned toward the storm's center after the center passed by. This helped him remain in less confused seas. He wanted to experience seas from only one quadrant.

Never allow a storm to pass directly over you offshore unless you want to be pummeled by seas from every direction.

WHEN YOU MAKE A MISTAKE AND GET CAUGHT IN A STORM, HERE'S WHAT TO DO:

1. Deploy a parachute. A parachute stops your boat reducing your kinetic energy to zero. It decouples the storm's energy from your yacht. It holds the bows into the wind and seas making it harder for the storm to take control of your yacht.

Parachutes work exceptionally well with catamarans. The wide beam of a cat allows the use of a bridle that keeps the bows of the cat pointing directly into the seas. Furthermore, there is no rolling of the catamaran when lying to a parachute sea anchor. We have used a parachute sea anchor only one time, and it was pure magic. It turned a bad situation into a "no worries mates" situation.

2. Deploy a drogue. Drogues slow your boat down and may even protect against wave strike in breaking seas if you use a powerful drogue. The Jordan Series drogue is extremely powerful, and if your stern and cockpit can handle breaking seas. the Series Drogue can maintain your kinetic energy at safe levels even with a major wave strike. Drogues work well on catamarans for several reasons. The twin hulls of the catamaran impart exceptional directional stability to the yacht, and the cat will run downwind like it's on railroad tracks. Furthermore, the following seas are able to slide under the elevated bridge deck rather than climb on board. Seas that might climb up the stern and fill the cockpit of a monohull will pass harmlessly under the bridge deck of a cat.

Storm management is about energy management. If you control the energy of your yacht, and if you decouple the energy of the storm from your yacht, the odds of survival are in your favor.

SEA ANCHOR CHAINPLATES

I've heard some experts say that the forces generated by the pull of a parachute sea anchor will pull your cleats right out of the deck. If you attach the parachute bridle to the cross beam of your catamaran, it will pull the crossbeam out of the bow.

I created my own answer to this objection. If you examine these pictures, you will see the parachute sea anchor chainplates that I put on my bows for use during storms, and I also sometimes use them at anchor in harbors if a major storm is headed my way. They create a chafe free way to attach a bridle to Exit Only.

These chainplates are twenty-five inches long on deck and consist of six millimeter thick stainless steel. On the underside of the deck is the same size of stainless plate, but it is only twenty inches long. Large bolts go through the deck and through both chainplates, and there is nearly zero chance that these chainplates will ever move. If they move, it's because both bows will have been pulled off the boat.

Welded down both sides of the chainplate and sticking out in front of it is a stainless steel bail that is about as thick as my finger. The part of the bail that sticks out in front of the bow is where I attach my parachute bridle using d-shackles that I wire closed after the bridle is in place. The bridle has large stainless steel thimbles on it so there is no chafe on the arms of the bridle where they are shackled to the bails.

When we left New Zealand expecting to get hit by a low pressure area or caught in a squash zone, I attached my parachute bridles to the bail of the parachute anchor chainplate on each bow before I left port. Everything was ready to go if we needed to deploy the chute. When we got caught in the squash zone, we shackled the parachute sea anchor rode to the already attached bridle and we quickly and easily deployed our parachute. It wasn't that big of a deal because everything was prepared in advance and we had tons of confidence in our gear and boat.

The bail that is welded to the sea anchor chainplate proved to be immensely strong. When we were anchored in Bequia in the Caribbean, a 115 foot long charter power yacht lost control of their vessel while raising anchor, and they plowed into our port bow. Fortunately, the sturdy bail on the sea anchor chainplate acted like a bumper putting a dent in their wayward bow which protected us from any damage to our hull. I have no doubts about the strength of our sea anchor chainplates and welded bail on our bow because it easily absorbed and survived the hit by that mega yacht. Our chainplates and sea anchor bridle system isn't going anywhere.

The bail was also useful when we were crossing the Indian Ocean dodging giant logs after the tsunami. We occasionally hit tsunami debris that was small, but when we got into logs that were bigger than our boat, I had to do something to protect our bows in the event of a collision with a tree. I used two long wooden oars to protect our bows. I passed the handles of the oars vertically through the bails on the bow, and then I lashed the oars into place. So I had heavy duty oars running down the full length of the bows, and if we hit anything, the oars would take the impact and spread the force of the impact so a hull penetration would not occur. One oar survived intact, and the other oar ended up being badly splintered by the time we were through the tsunami debris field. Even with those precautions, we still had some tsunami related bow damage.

If we did not have those bails sticking out in front of our bows, we would not have had a place to securely attach those oars on the front of our bows. It's quite possible that we could have had some major tsunami related damage if those oars couldn't have been lashed in place.

I love my sea anchor chainplates and bails. They saved me north of New Zealand in a squash zone, they saved me from serious tsunami damage in the Indian Ocean, and they saved me when I was hit by a mega yacht in Bequia.

Heaving To - The Venturesome Voyage of Captain Voss

If you want to read a good book that tells about heaving to as a way of decoupling your boat's energy from the energy of stormy seas, read "The Venturesome Voyage of Captain Voss." It's an awesome story by a man who sailed in the high southern latitudes and mastered the art of heaving to. He did it often, and he did it well.

Heaving to works because it does two things. It reduces your boat's kinetic energy as close as possible to zero, and it creates a protective slick to windward (a zone of turbulence in the water on the windward side of your boat) as you slide to leeward in a square drift. Energy waves don't propagate well into that slick zone of turbulent water and plenty of mariners will testify that approaching waves die out when they hit that turbulent zone of water to windward when they are properly heaved to. They report that breaking waves pass in front of the boat and by the stern, but the waves coming toward their beam diminish significantly in the zone of turbulence. That zone of turbulence is a killer of breaking seas, in a similar manner to the zone of turbulence behind a ship where the seas are quite flat although surrounding seas are large.

The protective effect of parachutes comes from three factors. First, the chute takes your kinetic energy down close to zero since your speed is close to zero. Second, because it holds you relatively stationary, it's harder for the seas to transfer their energy to your yacht. And third, the parachute creates turbulent water - a turbulent slick - directly to windward, and seas coming from that direction lose their power when they traverse the disturbed water created by your chute. When you look at an aerial photo of a parachute sea anchor at work on the cover of the Drag Device Data Base book, you can see the parachute close to the surface being slowly dragged through the water in front of the yacht. When we used our chute we dragged the chute about a half to three-quarters of a mile in 19 hours. I am sure the chute created a zone of turbulence to windward directly in front of our yacht, and I suspect that it helped diminish the power of oncoming seas. It kind of puts you in an "Alley of Lower Energy" that saps the strength of oncoming seas. You are in the zone of disturbed water that becomes your port in the storm.

Parachutes work extremely well on our catamaran, and I am not sure which of the three effects are most powerful during a storm. It's likely that all three effects are important to some degree, and they are cumulative as well.

Read the Venturesome Voyage of Captain Voss and be amazed at the power of heaving to. I am sure that Captain Voss would say reduce your kinetic energy as close as possible to zero by heaving to, and then watch the turbulent slick to windward protect your boat from the power of oncoming seas.

WHEN TO DEPLOY CHUTES AND DROGUES

Don't wait until it's blowing seventy knots to deploy a parachute or drogue. If weather fax and all available information indicates that you will be in serious trouble, it makes sense on a boat like Exit Only to deploy the chute while it's still easy to do. Its similar to preparing for a tropical depression or hurricane when you are anchored in a harbor. You know what is coming, and you don't wait to go out and anchor until it's blowing sixty knots.

If it became necessary to change strategy from a parachute to a drogue or vice versa, I was prepared so that deploying them wouldn't be an ordeal. When I headed offshore, I had the chutes, drogues, and all associated gear pulled out and ready to hook up and deploy before I set sail. If I needed it, I would pull the gear out of my salon, assemble it in the cockpit and rapidly deploy it.

Deploying a parachute was easy because I already had a bridle attached to my bow before I headed offshore. Deploying a drogue was easy because I was in a catamaran with port and starboard winches in the back of the boat and setting the drogue was quick and easy.

The ease of deployment depends a great deal on preparation and how you have set up your system. For us, all the components were available and ready to go. All I needed to do was assemble the components with shackles and seizing wire.

ALL YOU CAN DO IS ALL YOU CAN DO, BUT ALL YOU CAN DO IS ENOUGH

Don't wait until you're in a storm to figure out how you'll deal with it. Make your preparations ahead of time and have a plan. Storm survival isn't rocket science; it's mostly common sense. If you have a seaworthy vessel, a parachute, a powerful drogue, and don't panic, the odds are in your favor, and you'll the survive the savage seas. So drop your dock lines and pull up your anchor. It's time to sail on the ocean of your dreams.

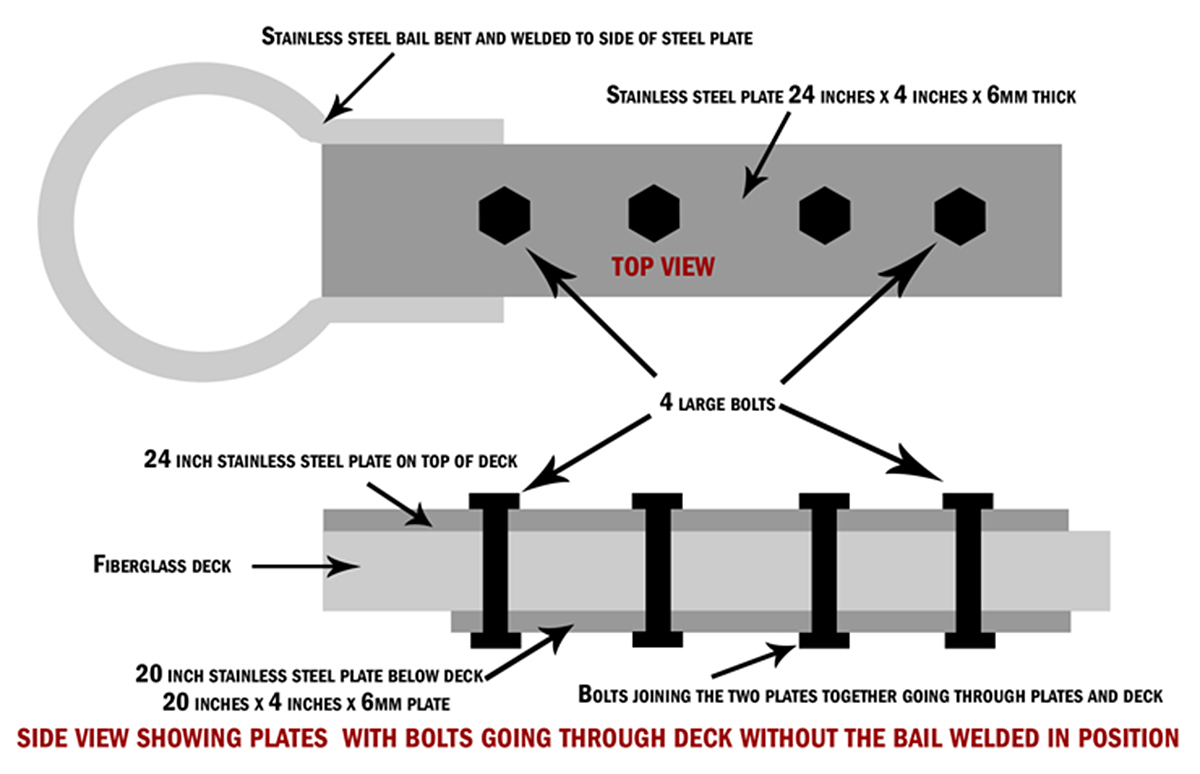

SCHEMATIC DRAWING OF MY PARACHUTE SEA ANCHOR DECK CHAIN PLATES

Some people have requested a schematic drawing of my parachute sea anchor deck chainplates that I had fabricated in Whangarei, New Zealand. The chainplates were made of stainless steel flat bar, and the bail was made of stainless steel rod. The rod was bent into a round shape and then welded down the sides of the chainplate. The dimensions of the stainless steel flat bar are as follows.

The flat bar on the deck as approximately 24 inches x 4 inches x 6 mm thick.

The flat bar backing plate under the deck was approximately 20 inches x 4 inches x 6mm thick.

The parachute sea anchor chainplates are definitely overkill, but they are a fool proof, chafe free way to attach a parachute sea anchor bridle on our catamaran. They will never pull out of the deck with the four large bolts going to the large backing plates.

Awesome music video that captures the essence of what it's like to sail offshore in a catamaran around the world when conditions are less than perfect. David Abbott from Too Many Drummers sings the vocals, and he also edited the footage from our Red Sea adventures. This is the theme song from the Red Sea Chronicles.

Sailing up the Red Sea is not for the faint of heart. From the Bab al Mandeb to the Suez Canal, adventures and adversity are in abundance. If you take things too seriously, you just might get the Red Sea Blues.

If you like drum beats, and you like adventure, then have a listen to the Red Sea Chronicles Trailer.

Flying fish assault Exit Only in the middle of the night as we sail through the Arabian Gulf from the Maldives to Oman. And so begins our Red Sea adventures.

Sailing through Pirate Alley between Yemen and Somalia involves calculated risk. It may not be Russian Roulette, but it is a bit of a worry. Follow Team Maxing Out as they navigate through Pirate Alley.

Stopping in Yemen was just what the doctor ordered. We refueled, repaired our alternator, and we made friends with our gracious Yemeni hosts. We also went to Baskins Robbins as a reward for surviving Pirate Alley.

After you survive Pirate Alley, you must sail through the Gate of Sorrows (Bab Al Mandab) at the southern entrance to the Red Sea. The Gate of Sorrows lived up to its name with fifty knots of wind and a sandstorm that pummeled Exit Only for two days. Life is good.

Although I like the feel of a paper book in my hand, I love trees even more. When people purchase an eBook, they actually save trees and save money as well. Ebooks are less expensive and have no negative impact on the environment. All of Dr. Dave's books are available at Save A Tree Bookstore. Visit the bookstore today and start putting good things into your mind. It's easy to fill your mind with positive things using eBooks. No matter where you are or what you are doing, you can pull out your smart phone or tablet and start reading. You can even use electronic highlighters and make annotations in your eBooks just like paper books.